This is the second half of my description of the silk-weaving industry in Venice. The first post covered some general Venetian history; this one describes a Venetian silk-weaving workshop still in production today.

The Tessitura Bevilacqua

The retail storefront in Venice of the Tessitura Bevilacqua.

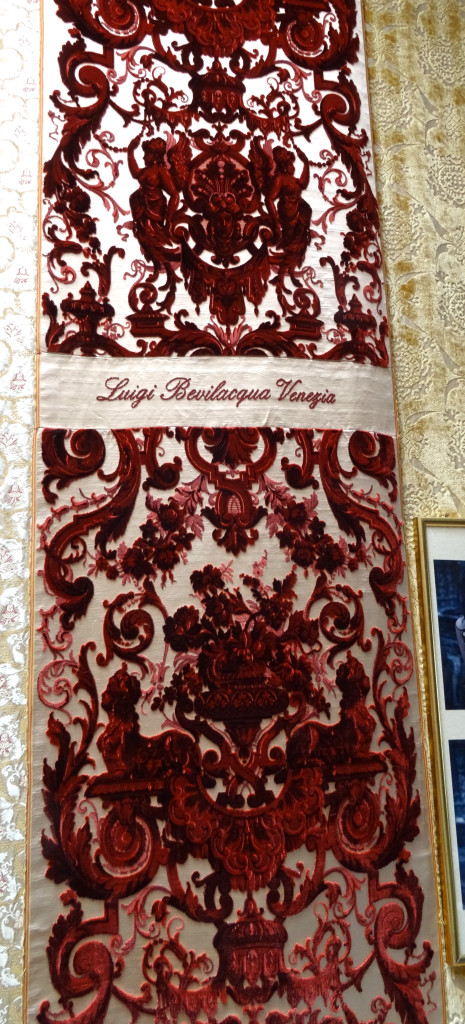

In 1875, Luigi Bevilacqua took over the equipment, materials and workers of a textile-manufacturing establishment on Venice and began his own family-run silk-weaving company. The Tessitura Bevilacqua received immediate and sustained accolades for the quality of its velvet-weaving. Working on 18th century drawlooms, expert weavers made velvet both to reproduce old patterns but also brought in contemporary designs to stay fresh and relevant. By the end of the 19th century they had set Jacquard machines on top of the drawlooms to replace the drawboys selecting the weaving sheds. Going into the 20th century, they incorporated movements such as Art Deco into their textiles and worked with contemporary designers.

Despite the luxury prices and the long wait for handwoven Bevilacqua fabric, business remained steady. Over the 20th century, their cloth was ordered to adorn the government buildings and palaces of many countries in Europe, as well as theaters, hotels, and churches. The Vatican is a major client, and there have even been Bevilacqua velvets in the White House, hung as curtains in the Yellow Room in 1983.

Velvet Weaving

Loop plus cut-loop pile velvet being woven; metal rods hold the supplementary warp threads in pattern.

Velvet weaving is a special technique that results in either loops or pile (cut loops) above a ground cloth. Usually these are arranged in a decorative pattern, which can be quite ornate. The loops are made from supplementary warp threads that are pulled up through and secured by the ground warp and weft. The loom is set up with the ground warp in the regular configuration, stretching from the back beam to the front, and the supplementary warp carried on spools underneath the ground warp threads. The Jacquard mechanism causes a shed to open when the treadle is pressed. For a pattern shed, some of the supplemental warp threads are raised and secured by placing a metal wire into the shed. To simplify, this process is repeated until the loop has been locked into the fabric by several picks. Then, if the loops are to remain, the rod is removed; if a cut pile is desired, a special cutter is used that fits into a small groove in the wire so the fibers are cut precisely.

The weaver uses a special cutter that fits into a groove in the metal rod holding the pattern threads; this makes a precise and clean cut.

The Bevilacqua Weaving Workshop

The entrance to the Bevilacqua workshop.

I arranged a tour of the handweaving workshop (see Practical Matters, below) and arrived to meet Gloria D’Este, one of the Bevilacqua weavers and my tour guide. It was great to see a young person having the opportunity to work full-time as a weaver. “I love my job,” said Gloria when I commented on this. “Every day I come here and I am so happy to be here.”

Jacquard cards already used for pattern weaving.

The tour began with the warping equipment and an impressive collection of old and dusty Jacquard punched cards.

Warps are measured on the large vertical warping mill. Gloria said that usually warps are a natural or white color, but they were working on a special order at the time requiring the red threads.

Once the warp is wound, it is removed from the vertical mill by winding it onto the horizontal mill. From there, it is wound onto a warp beam, which is carried to the loom and put in place. As any weaver knows, all of this winding is done to ensure perfectly even tension in the warp once it is fixed to the loom. I was fortunate to see almost all the phases of warping and weaving during my short visit, as I almost walked into the warp threads being wound onto the warp beam as I was leaving!

After the warp is wound onto the vertical mill (at left) from the spool rack (lower right), the completed warp is wound onto the large horizontal mill (upper right), before being re-wound yet again onto a warp beam.

Most Bevilacqua velvets are made with silk, but they do use some cotton when the purpose of the fabric calls for it. Some upholstery fabric is made with cotton, as well as some of the fabric that is destined for sale in their retail shop in order to have some more affordable choices.

Next, Gloria showed me the Jacquard card-punching station. Before the advent of computers, all pattern cards were made by hand in this way. Looking at the pattern, the worker would place pins in the proper holes. When the block was done, a card was laid over the pins and pressed down to make holes in the card. Each card contains data for half a millimeter (!) of woven velvet and hand-punching the pattern cards for a full pattern repeat took three to four months. The cards would only last so long and would then need to be made again. Now, of course, all the patterns are stored in computer databases and the cards are printed out as needed.

Gloria D’Este, Bevilacqua weaver and my tour guide, demonstrates the use of the old Jacquard card-punching equipment.

Card-punching equipment for Jacquard machines.

Computerization is one reason why the number of weavers at the workshop has dwindled to five since the early days when there were dozens of people employed as weavers, warpers, card punchers, and other workers. In the past, each person had a single job, such as winding warps or punching cards. Now, because computers have taken over much of the design work, each weaver is involved in the whole process. Also, Bevilacqua opened up a weaving factory on the mainland nearby where many of their designs are made by machine, reducing the workload for the handweavers. The main reason that handweaving still exists in the company is because there is one type of velvet that must be done by hand. The machines can make looped velvet, or they can make cut pile velvet, but they cannot incorporate both within the same design. Like crochet, or nupps in knitting, it is an indicator that the fabric is handmade.

New warps are almost always tied onto the old ones, because the patterns can be changed by merely changing the Jacquard cards. Cotton threads are tied together with a weaver’s knot, but the fine, slippery silk threads are twisted together with a special adhesive. The supplemental warp threads are carried on spools below the ground warp threads.

Warp threads (gold) and supplementary warp (pink).

The threads rise gracefully up to the heddles and the two colors, ground and pattern, meet and pass through the shafts.

Viewed from above, the supplementary threads approach the ground warp in either a peak (^) or wing (\) formation. When the peak form is used, it means that the resulting pattern will be a ‘butterfly’ or symmetrical pattern where the left and right sides mirror one another.

When the wing form is used, then all of the threads can be manipulated independently and a non-symmetrical pattern can be formed. This type of pattern allows realistic shadowing to be incorporated into a pattern.

One of the orders recently made was for the Kremlin and was a reproduction of a 200-year-old velvet pattern. Making this cloth involved creating the pattern in the computer, setting up a loom with over 12,000 warp threads, and having two weavers working at once—one to manage all the weight of the heavy harnesses on the treadle, and one to weave the threads. In this way, two weavers could weave 25 cm each day. For that amount of work, €5000 per meter seems more than reasonable.

On the ‘regular’ looms, one weaver typically completes 35 cm per 8-hour day–an improvement, albeit a modest one.

In the front, or canal-side, of the building, there is a showroom accessible by boat on the Grand Canal. This is where customers placing special orders meet with the Bevilacqua staff and plan their fabric, whether it is a reproduction of an antique velvet or a new pattern based on a designer’s vision.

The fabrics are simply stunning, with a heavy, soft hand and beautifully complex patterns. I was especially impressed with the tiger-skin and leopard-skin replicas. They are so realistic both in look and feel that during the initial encounter, one would be hard-pressed to say whether it was real or reproduction.

Gloria showed me one example of how Bevilacqua works with fashion designers to make the fabric for their runway designs. The designer came to them with an image they wished to be evoked by the cloth:

The staff at Bevilacqua studied the image (wider print underneath the top page) and came up with a design that could be woven and would faithfully represent the original artwork (top page). Then the weavers made the velvet.

The result was this concept fashion:

The result was this concept fashion:

I was sorry when my tour ended, but I knew I had to let Gloria get to work on her 35 cm of velvet for the day, and I had more of Venice to see.

Later that day, I visited the Santa Maria della Salute, which was completed in 1687 A.D.

The church was built because, during a plague epidemic, the Doge prayed to the Virgin Mary and promised that, if the plague was stopped and Venice saved, there would be a new church built dedicated to health. There are lots of churches in Venice; I mention this one because upon entering, I discovered this:

The church was built because, during a plague epidemic, the Doge prayed to the Virgin Mary and promised that, if the plague was stopped and Venice saved, there would be a new church built dedicated to health. There are lots of churches in Venice; I mention this one because upon entering, I discovered this:

Yes, that is Bevilacqua velvet adorning those pillars. You can learn more here.

Yes, that is Bevilacqua velvet adorning those pillars. You can learn more here.

Practical Matters: Touring Bevilacqua

The handweaving workshop is still on the island of Venice at 1320 Santa Croce and employs five weavers. If you are interested, you can contact them via their website to arrange a private tour, available by appointment only. If you are just visiting Venice and don’t really know your way around, the easiest way to get there is to take the #1 vaporetto (water bus) and get off at Riva de Biasio on the Grand Canal. From the vaporetto stop, you will need to go immediately left, turn right when that street ends, and then walk in a horseshoe-shaped pattern by always turning left, being sure to not go over any bridges (use Google Maps to get a visual on this). You will end up at the entrance to the workshop, pictured above.

There is also a Bevilacqua retail shop near San Marco, and another near the Bridge of Sighs. If you don’t have the time or inclination to arrange the workshop tour, you will at least be able to see the amazing fabrics. Souvenirs are pricey, though: a small throw pillow is hundreds of Euros!