While in Venice this summer, I had an interesting foray into what you might call the opposite of thriftiness and recycling in weaving. Bear with me as we get lost for awhile in the world of conspicuous consumption, whose redeeming factors include an incredibly high level of artistry and a long and rich historical tradition.

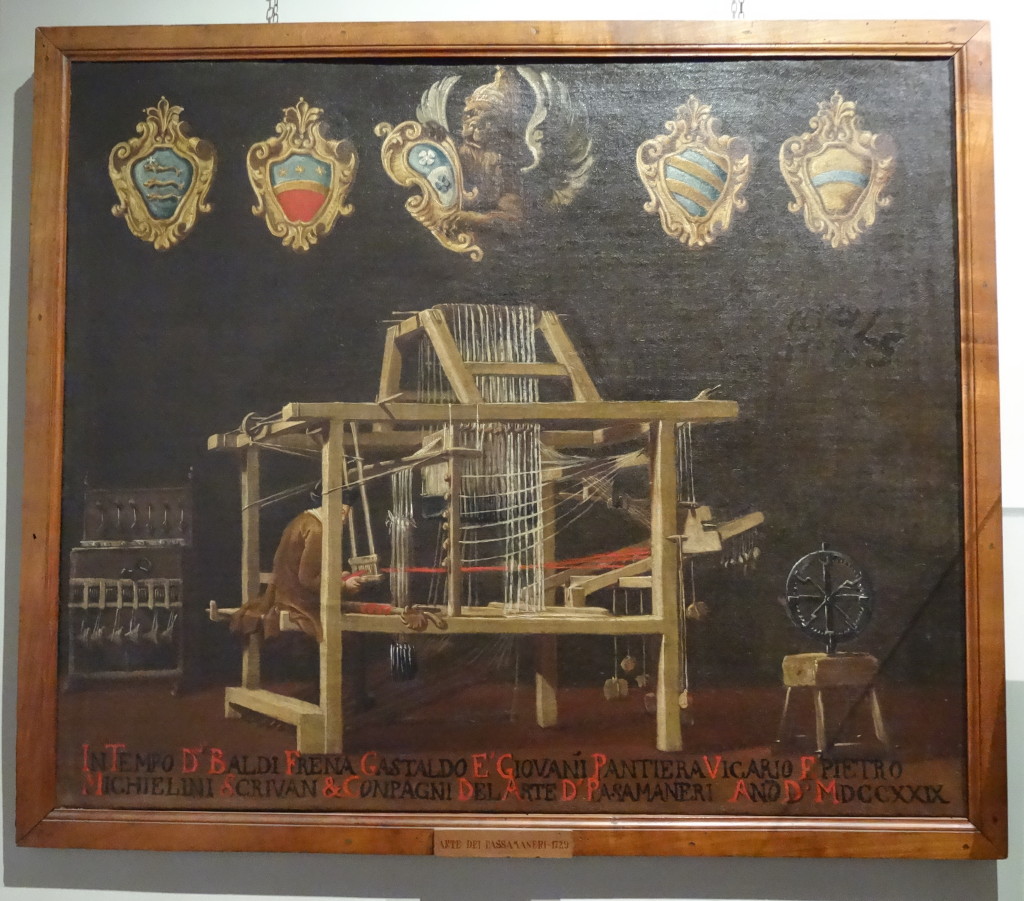

Venetian History and Silk Weaving

Venice, as most people know, is now a city in Italy, but at one time it was in and of itself a major world military and economic powerhouse. The Venetian empire lasted from the late 7th century A.D., when it organized the lagoon cities of northeastern Italy in self-defense as the Western Roman Empire was fading, until Napoleon conquered it in 1797. At its height, it dominated trade routes to the east and had close ties with the Byzantine Empire, which are reflected in the Eastern style of architecture in the Doge’s Palace and other buildings.

Doge’s Palace, Venice

Venice became wealthy beyond belief, secured by a navy so powerful that for centuries no one dared challenge them on sea. Part of the navy’s might came from a shipyard on Venice that could produce, in a single day, a complete battle ship ready to be manned and sail.

The Arsenale di Venezia, where at its height, the Venetian Navy could add one ship per day to its fleet.

Like all empires, Venice had a decline, in this case at the hands of the Turks, who diminished and conquered the Venetian navy and took outlying islands and territories until the empire was limited to the lagoon area and part of northern Italy. Napoleon came along and occupied Venice in 1797 with little effort. After some back-and-forthing as an Austrian province and an independent republic, it finally settled in as part of the new Kingdom of Italy in 1866.

Venetian lace, Museo Correr.

Venice became famous during the Middle Ages for its highly skilled artisans and the goods they produced. Everyone has heard of Venetian lace (which is actually made on the nearby island of Burano) and Venetian glass (which is actually made on the nearby island of Murano), but perhaps not as many people have heard of the Venetian silk-weaving industry and Venetian velvet (which was actually made on the island of Venice).

Silk weaving in Venice had its origins in its extensive trading with the East, beginning with Marco Polo (a Venetian), who returned to Venice from China at the end of the 13th century and lived there until his death in 1324. The timing of the rise of silk-weaving in Venice coincides with Marco Polo’s return, but also with an influx of weavers fleeing the Tuscan city of Lucca in 1309. These weavers were welcomed into the city and given a place to live and work, since it was recognized that the exchange of information and ideas between them and the Venetian weavers would be beneficial. Whether or not velvet weaving was already taking place on Venice, the Luccan weavers brought knowledge and skills to help the industry grow.

Examples of Venetian silk-weaving from the 15th-18th centuries; Museo Correr.

Silk velvet weaving in Venice continued to rise during the 14th century. Soon it became highly regulated—everything from who could weave, what they could weave, the width of the cloth, the dyes used, to the number of warp threads per centimeter (at least 96) was subject to stringent standards and oversight. Demand was high and sales were good. Venetian velvet was carried by Venetian merchants throughout their trade routes in Europe and the Byzantine Empire.

The Napoleonic administration disbanded all craft corporations in Venice when they took over to reduce competition with French craftsmen. This didn’t mean that the craft industry died overnight, but it did fade gradually away under this unfriendly regime. By 1811 a statistical report described the silk industry as in ‘dire decay’. Through the 19th century, there was some effort to join the Industrial Revolution and become a center for manufacture of lower-quality goods at competitive prices, but the only companies surviving this time period were niche crafters making high-quality, artistic goods. Perhaps Venetians, with their grand history, were not cut out for factory work.

In my next post, I’ll tell you about my tour of a workshop in Venice that is still producing handwoven velvet today.